There is a moment in “The Double Life of Véronique” when Irène Jacob’s character stretches her hand out of a car window to feel the wind. The camera lingers. Her fingers respond not to anything she sees, but to what she intuits. This gesture, simple and wordless, captures the heart of Krzysztof Kieślowski’s cinema: a world where emotion precedes narrative, and feeling is its own kind of truth.

Kieślowski’s films do not unfold in the usual sense. They unfold through us. In an age of cinema driven by urgency, his work slows time, asks us to listen, and reminds us of what lingers in silence. If modern streaming culture rewards the binge, Kieślowski invites the breath. Watching “The Double Life of Véronique” is not about decoding a mystery. It’s about surrendering to one.

In “The Double Life of Véronique” (1991), two women, Weronika in Poland, Véronique in France exist in mirrored realities. They do not know each other but feel each other. One dies; the other suddenly retreats from her musical path, moved by a sensation she cannot explain. These women are not metaphors. They are emotions personified. Their duality isn’t science fiction or spiritual doctrine. It’s about the uncanny resonance we sometimes feel with strangers, with places we’ve never been, or songs we’ve never heard before that seem to know us.

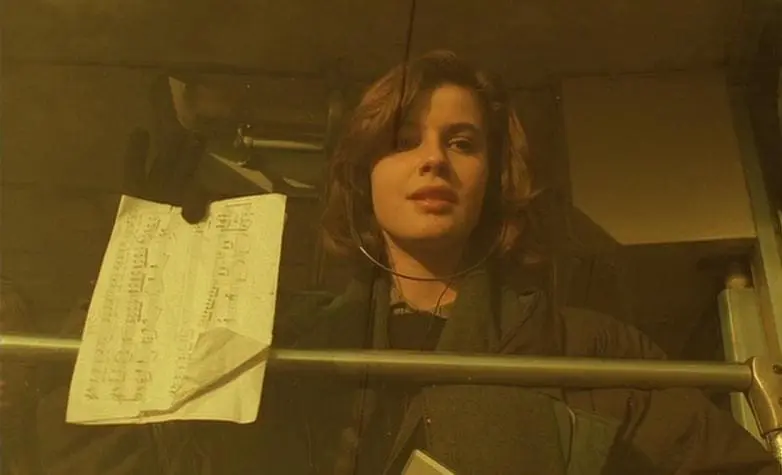

The film’s visual language is soft, saturated with green and gold filters, the light often dappled or refracted through glass. Kieślowski and cinematographer Sławomir Idziak don’t use the camera to observe; they use it to feel. Paired with Zbigniew Preisner’s melancholic, otherworldly score, Véronique becomes a symphony of intuition. Objects carry weight: a marble, a puppet, a thread. The tactile becomes spiritual.

There is little dialogue. Véronique moves through her world, attuned to signs, glances, and textures. The film doesn’t offer a resolution, but rather resonance. It is perhaps the purest expression of Kieślowski’s shift from his earlier political documentaries and social dramas toward something metaphysical, internal, and more elusive.

To understand Véronique is to enter Kieślowski’s greater thematic universe. In “Dekalog,” his ten-part television masterpiece, he maps moral dilemmas onto everyday life in Poland. In “Three Colours: Blue, White, Red”, he abstracts liberty, equality, and fraternity into personal grief, revenge, and spiritual connection.

Yet across these varied films, Kieślowski’s signature remains: the notion that our lives are shaped not only by choice, but by chance, coincidence, and the intangible fabric of human connection. A missed bus, a glance, a dream, these are the hinges on which his stories turn. In “Blind Chance”, a man’s future unfolds in three divergent paths depending on whether he catches a train. In “Red”, a young woman and an ageing judge seem cosmically entwined despite never having met.

Kieślowski’s characters are rarely in control. They are moved, often inexplicably, by forces they cannot name. It is in this surrender to feeling over logic, to mood over message, that his films resonate most deeply.

In today’s cinematic landscape, where algorithms push content based on what we’ve already consumed, Kieślowski’s cinema feels quietly rebellious. He resists explanation. He asks for patience. He asks us to notice the light as it bends, the breath before the decision, the music before the word.

The resurgence of interest in his work, spurred by 4K restorations, Criterion reissues, and retrospectives, coincides with a broader longing among audiences for more contemplative, sensory experiences. The rise of “slow cinema” (think Apichatpong Weerasethakul, Kelly Reichardt, Joanna Hogg) reveals an appetite not just for story, but for presence.

In a culture of instant reaction, Kieślowski offers duration. His films echo. They haunt. They return in moments when we, like Véronique, stretch our hands into the wind and feel something we cannot name.

Kieślowski once said, “I try to make films about people who have something inside, who don’t always express it, but who feel something.” His films are not puzzles to be solved, but mirrors to sit with. In “The Double Life of Véronique”, the mirror reflects more than a face; it demonstrates a soul in echo.

As cinema becomes faster, louder, and more didactic, returning to Kieślowski is not nostalgia, it’s a necessity. He reminds us that film can be a vessel for the things we don’t know how to say. Some stories are best told in glances, threads, and refracted light. That to truly see is, sometimes, to feel.

A Playlist of Music from the Films of Krzysztof Kieślowski

Zbigniew Preisner’s compositions are inseparable from the emotional landscape of Kieślowski’s films. This short playlist offers an atmospheric companion to the moods explored in this piece — memory, silence, fate, and the unnamed.

Best experienced on headphones, in stillness.

Curated by HYGY

Spotify playlist