Words by Lola Carron

Edited by Valerie Aitova

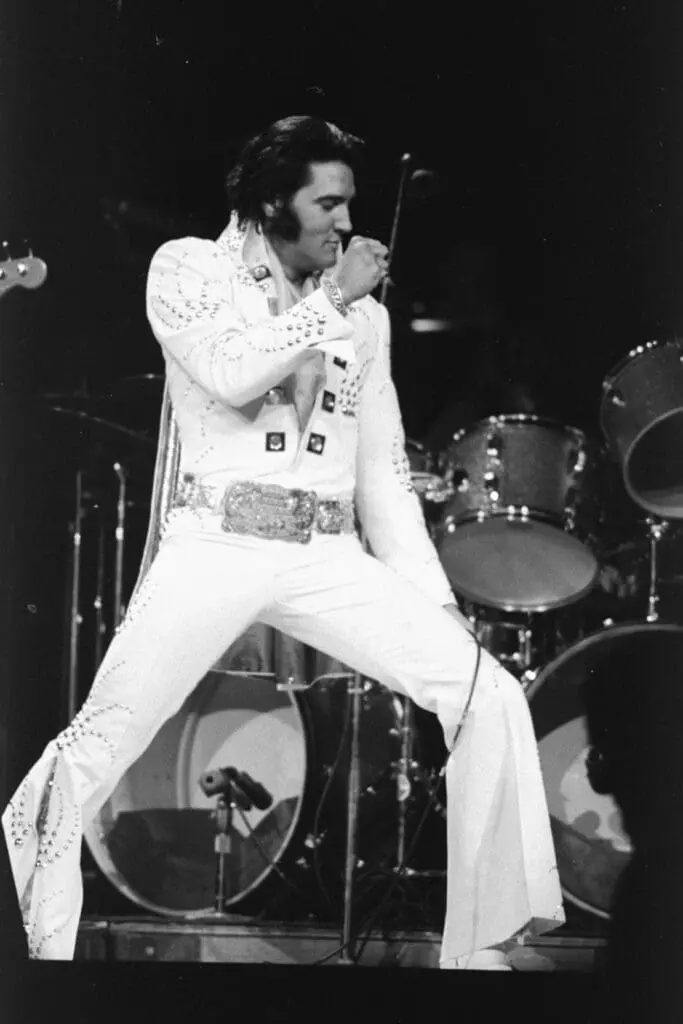

Music and fashion have always shared a stage. Elvis Presley’s slick suits come to mind, as do Madonna’s cone bras and Prince’s purple everything. The two industries have long been intertwined, each riffing off the other’s rhythm. But somewhere between the merch stands and the Met Gala, the relationship evolved. Artists no longer just throw on a designer look for the red carpet because their stylist said so. They’re not mumbling “I’m wearing Rick Owens tonight” with a shrug. They want to be part of the world their clothes belong to: to shape it and become unmistakable within it. We’re not questioning whether musicians influence fashion, it’s whether they can create a visual universe of their own.

It’s easy to forget that the first wave of musician-led fashion wasn’t built on hype, but on rebellion. Elvis’s sharp tailoring was a quiet act of defiance in a world of conformity. David Bowie’s glam-era jumpsuits blurred gender lines before it was marketable. Even Kurt Cobain’s torn cardigans were a protest against polished celebrity culture. These artists used how they dressed as extensions of their sound. Every look was a lyric, every silhouette a statement.

Then came the millennium, and the crossover turned commercial. Hip-hop culture, which had long defined streetwear’s language, began shaping luxury itself. In the 1980s, Run-D.M.C. turned Adidas into a symbol of identity within hip-hop culture, making sneakers a cornerstone of personal expression. Kanye West later made trainers as talked about as his music, and Rihanna redefined beauty and body inclusivity through Fenty, crafting a fashion empire that felt less like a side project and more like a revolution. These were the artists who proved that a brand could become an album, using fashion as an extension of voice, not an accessory to fame.

But not every attempt hit the right note.

Fenty remains the gold standard, not just a celebrity brand, but a cultural reset. Rihanna didn’t license her name; she built an empire that redefined what inclusivity could look like in both fashion and beauty. From foundation shades to lingerie lines, she turned representation into a business model. For every Fenty, though, there’s a half-hearted capsule that vanishes faster than a remix drop, an echo of authenticity rather than the real thing. Justin Bieber’s Drew House might have sold hoodies, but it’s often been critiqued for lacking the narrative depth of brands like Fenty. Travis Scott’s expansive merch empire has blurred the line between art and marketing, with some fans suggesting it’s more commerce than creativity. In music, you can’t fake soul; in fashion, you can’t fake intention. The most successful crossovers happen when a brand feels like an artist’s world made tangible, not a licensing deal disguised as creativity.

The key lies in translation. Authentic artist-led fashion is about turning sound into texture. Tyler, the Creator’s GOLF le FLEUR makes his pastel-toned eccentricity wearable and, yet perfectly composed. Billie Eilish’s oversized silhouettes capture the intimacy and unease of her music: protective, personal, defiantly anti-glamour. Rosalía, meanwhile, doesn’t need a label to prove her point as her motocross-inspired stage wear and red-lacquered attitude have become instantly recognisable and deeply tied to her music, influencing how Spanish pop artists dress globally. The same goes for Peggy Gou, the Berlin-based DJ-turned-designer whose label Kirin translates club energy into high-octane streetwear collections. Their brands work because they don’t just echo their music; they expand it.

And then there are the fans who take the role of the true co-authors of this story. The modern listener doesn’t just want to stream their idols; they want to inhabit them. Wearing a piece of Fenty or Golf le FLEUR isn’t about consumption, it’s communion. Gen Z audiences, raised on TikTok trends and micro-aesthetics, curate their wardrobes like playlists. Fashion becomes a new language of fandom: a way to signal loyalty and selfhood at once. As one stylist recently said: “It’s not merch anymore, it’s a uniform.”

But that same intimacy can turn volatile when it feels inauthentic. Fans, especially younger ones, have a built-in radar for branding that rings false. When an artist drops a fashion line that feels corporate or algorithmic, the reaction is immediate, disinterest at best, backlash at worst. The relationship between fan and artist has shifted from aspirational to participatory; audiences want to feel seen, not sold to. You can see it in how genuine artist-led pieces, from tour merch to limited capsule drops, sell out within minutes, driven by fans who feel they’re buying into a shared world rather than a marketing ploy. In the era of parasocial connection, authenticity isn’t just desirable; it’s curre

Still, fashion remains both a mirror and a gamble.

The best musician-led lines succeed because they expand on an existing story, not because they’re trying to start one. Beyoncé’s Ivy Park channels her discipline and precision. A$AP Rocky’s creative input at Bottega Veneta feels symbiotic, not forced. Meanwhile, other ventures, though slickly produced, collapse under their own weight, too calculated to connect. In a world obsessed with image, overexposure might just be the new creative risk.

What’s next feels harder to define. As AI aesthetics and virtual identities reshape how artists connect with audiences, the future of musician fashion might not involve fabric at all. We’ve already seen hints of this: Travis Scott’s Fortnite concert spawned a wave of digital merch tie-ins; Grimes has explored digital wearables and virtual art drops; and entire fanbases now build DIY looks for avatars on digital stages. The next big collaboration might not be with a couture house, but a coder. The line between dressing up and logging in is fading.

The constant reinvention. For artists, fashion remains the loudest way to say something without speaking. For fans, it’s a way to listen without sound. And maybe every artist eventually becomes a designer, or maybe they already were. After all, the first thing you design isn’t a song or a collection. It’s a self.

And somewhere between all this, a question: what is your #HaveYouGotYours?